by Mike Roberts, Church Historian

In the past three segments [part 1, part 2, and part 3] we have explored the leadership that led our church to a firm foundation during its first fifteen years of existence. To fully understand the challenges to those leaders as well as to the growing congregation, we must explore the religious climate from the 1820s to the 1850s in the United States.

While we all know that religious freedom is guaranteed in our laws, in the hearts, minds and actions of those days, attacks on individuals and groups for their religious beliefs were quite common. Sometimes those attacks were even of a violent nature. Universalism had its roots in New England and was part of a liberal religious movement that included Unitarianism, Transcendentalism, Congregationalism and other splinter groups.

To the leaders and members of more rigid and doctrinaire Protestant religions, the beliefs of these rebels were considered a grave threat not just to their own view of religion but also to the very survival of the young country. Evangelical efforts by many Protestant sects were common in an attempt to bring in new converts and quash the growth of other religions. Camp meetings and revivals often reached a frenetic pitch. The sermons of ministers were frequently marked by attacks on other faiths and many religious groups fought even amongst themselves over the smallest of issues.

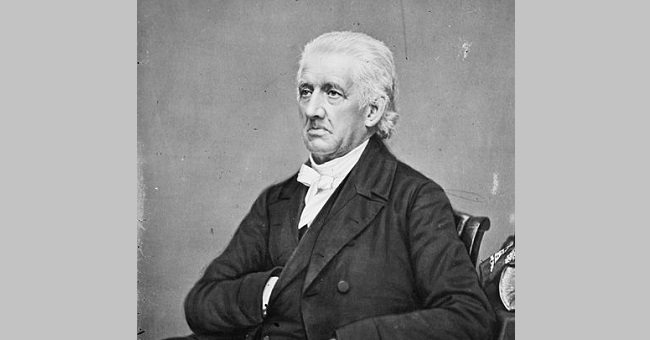

To illustrate the serious nature of these religious rivalries, it might be useful to study the life of Lyman Beecher. During the 1820s, Beecher was arguably the most prominent minister in the United States and is now remembered as a mighty abolitionist and the father of Harriet Beecher Stowe and Henry Ward Beecher. Harriet, of course, was the author of Uncle Tom’s Cabin. Henry followed his father to become the most famous preacher in the United States following the Civil War.

Lyman was a Presbyterian of the Calvinist brand and saw any other religious belief as a threat to the welfare of the entire nation. He was especially outspoken toward the Catholic Church. Shortly before leaving his New England home, Beecher spoke to a huge throng in Boston and castigated the followers of the Pope in Rome. That night, an Ursuline convent was burned to the ground in Boston.

Friends and professional colleagues urged Beecher to carry his fight against all usurpers of the faith to the next big battleground. That battleground was the frontier West and the capital of that frontier was Cincinnati.

In 1832, Beecher left New England and took the job of president of Lane Seminary, a school to prepare Calvinist ministers for the churches of the West. He worked in that position for ten years while at the same time serving as minister at the Second Presbyterian Church of Cincinnati. During his tenure at Lane, he preached the doctrine hundreds of times to large throngs and did all he could to suppress the liberal churches while at the same time continuing his assault on the Catholic Church.

As the years wore on, Beecher found as much resistance from his own factions as he did from other religious groups. In later years, his voice calmed a bit and he turned his attention to the abolitionist movement. Much more could be said about Beecher, but let it be known that his attempts to stall the spread of other religious thought had little effect while his opposition to slavery contributed greatly to that cause.

One more issue related to Universalism needs a short explanation. While our own church began to thrive in urban Cincinnati in the 1830s and 1840s, Universalism had its greatest growth in the small farm communities of the West. As an illustration, during this period, Universalist churches and preaching stations were established in Miamisburg, Princeton, Montgomery, Mason, Milford, Hamilton, Edwardsville, Mt. Carmel, Delhi, Sharon, Goshen, Dry Ridge, Indian Hill, and Plainville. In the 1850s churches were begun in Newtown, Amelia and Blanchester. The existence of these churches was the reason so many ministers took to the circuit to preach the Universalist message rather than remaining in one church. It also made it much more difficult for the Lyman Beechers to snuff out the expanding liberal faiths.

Thus, did our young church survive these assaults. Entering the 1850s, it numbered 330 members and had nearly outgrown its new church. On the horizon, another church was to be built on Plum Street and the country would be torn asunder by war, but for now, all was well and the church played a prominent role in the Queen City of the West.

Note: The Lyman Beecher House on Gilbert Avenue is open to the public during certain times. It is closed during the winter months.

Image: Lyman Beecher.

Image source: Wikipedia.