by Mike Roberts, Church Historian

In recent articles “From the Archives,” we have explored the life of the founding father of American Universalism, John Murray. His story would not be complete without an exploration of the life of his second wife, Judith Sargent Stevens Murray. Ms. Murray and her family played a critical role in John Murray’s life and in the establishment of Universalism in America. She also could easily be called the first lady of feminism in the history of our country.

Judith Sargent was born on May 5, 1751 in Gloucester, Massachusetts, the first of eight children of Winthrop Sargent and Judith Saunders. Her father’s family was involved in many businesses in the Gloucester area and they were considered to be influential citizens in the community and in the Congregational Church to which they belonged.

Judith displayed at an early age a strong intellect. However, in late 18th century colonial America, formal education was reserved for well-to-do-males. Judith, nonetheless, was composing poetry at age 9 and reading many books from the extensive family library. When her brother, Winthrop, was assigned a tutor to prepare him for entry into Harvard, Judith was allowed to attend these rigorous sessions and accumulated as much knowledge as most of the young men headed off to be educated at America’s first and foremost college.

At age 18 in October of 1769, Judith married John Stevens, a successful ship captain and merchant in the commercial trading business. This did not halt her desire to self-educate as well as to express her opinions through writing. As America went to war with Great Britain, she began to publish essays and articles in Boston magazines. Many of these articles dealt with women’s equality, education for girls and young women and financial independence for women. However, the societal norms of the day required that she publish all her works under pen names to disguise her own gender. These noms de plume included Constantia, The Reaper and The Gleaner.

Unfortunately, the war cost her husband his prosperity. He contributed greatly to the cause of the revolution and used his ships to bring much needed supplies to the colonies. By war’s end he was deeply in debt and was forced to flee the country to escape debtors’ prison. He went to the West Indies where he died leaving Judith a widow. She and her husband had no children.

It was during the post-war period that the Sargent family led its own revolution against the Congregational Church of Gloucester. Along with a number of other families, they eventually withdrew from the church, refused to pay their church taxes and formed their own congregation, calling themselves Universalists. Thus, the Universalist Church of Gloucester became the first in America. The Sargent family role in the establishment of Universalism also resulted in a romantic relationship between Judith and their first minister, John Murray. The two wed on October 6, 1788 in Salem, Massachusetts.

It was slightly over a year later that Judith published her most famous work, an essay “On the Equality of the Sexes”. She had actually written the work in 1779 but the war, her husband’s debt and ultimate death caused it to be put aside. However, she strongly felt that the foundations of a democratic America also included more rights for its female citizens and expounded on this in the essay. This important work was followed by a multitude of other essays, poems, several comedic plays and letters. Judith continued to write until a debilitating stroke felled her husband. The ill health he suffered lasted for years and Judith was consumed in taking care of her husband. She used the time to work on John’s own writing. She edited sermons and essays that he had written and also completed his autobiography after his death.

She and John had two children, a son who died in infancy and a daughter, Julia Maria, who married and moved to Natchez, Mississippi. After John Murray’s death, his widow moved to Natchez to spend the rest of her life with her daughter. She died there on June 9, 1820.

Judith left behind a wealth of work mostly on a subject which was not well appreciated in her day. She left her papers to the Mississippi state archives and they laid there for a century and a half until discovered in the 1980’s. The body of work is still being catalogued and analyzed to properly establish Judith’s place in feminist history. To illustrate the importance of her works, it could be pointed out that David McCullough used excerpts from one of her letters to describe Judith’s observations of John and Abigail Adams. Judith and John Murray visited the Adams couple while the Murrays were honeymooning in 1788. Cokie Roberts also quoted Judith in her book, “Founding Mothers,” describing Judith’s influence on Martha Washington. Roberts makes the point that both Abigail Adams and Mrs. Washington became supporters of greater rights and opportunities for women, and Judith connected with both women on this level. The Adams and Washington families considered the Murrays to be close and rewarding associates.

Judith’s work “On the Equality of the Sexes” has been used by many writers as a manifesto in seeking equal rights for women. She exemplifies so many women of the Universalist faith who have played major roles in their church and in society. They certainly had a worthy early role model in Judith Murray.

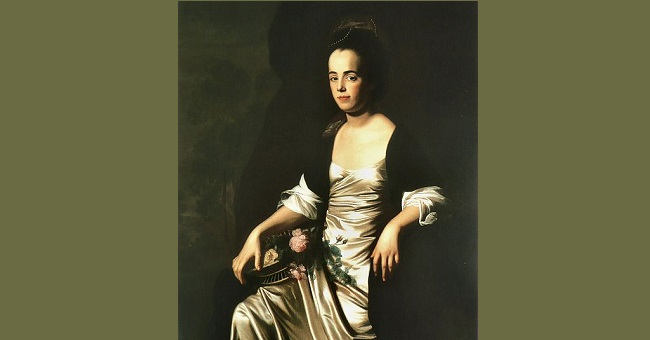

Image: Portrait of Mrs. John Stevens (Judith Sargent, later Mrs. John Murray),

by John Singleton Copley, 1770-1772.

Image source: Wikipedia.