by Mike Roberts, Church Historian

As the Civil Rights movement was heating up in the 1950’s, churches across the nation were thrust into the position of deciding their own stance on issues of race relations. The arguments around these issues became quite volatile at times. The central theme of these debates was integration of individual churches who belonged to national church organizations. During this period, the Cincinnati Enquirer published a number of articles on integration and the church. The one cited below is representative of what was being discussed and appeared in the August 27, 1955 edition of the paper. The author of the piece was Herman Allen.

“While most of the larger Protestant denominations have accepted the principle of racial desegregation in public schools, a distinguished religious news editor (of the Washington Herald) finds that the move toward an interracial church, particularly at the congregational level, has sturdy sincere opposition.”

Allen goes on to make the point that while many national church authorities supported desegregation of its churches, they lacked the power to enforce such a code at the congregational level. He also stated that government and social agencies were being forced to take the lead in an area that had been in the domain of church and religious authority in times past—namely the espousal of social justice issues and reforms. Some national organizations made powerful statements about their beliefs. That same year, the Episcopalian Church moved its triennial national convention from Houston to Honolulu because Houston could not guarantee that hotels and restaurants would serve all of the Episcopalian membership regardless of color or race.

In Washington DC, the Presbyterian Church of Northern Washington took a pro-integration stance that urged “all our churches to complete desegregation throughout the church and throughout the communities in which our churches work and serve”.

Several weeks later, the Rev. E. Les Weston of the Avondale, Maryland Baptist Church responded, “In the armed forces, in public works, in transportation and in similar things, integration is necessary and feasible. In close social relationships such as schools, churches, social clubs the practical solution would be segregation. I feel there is nothing unchristian or condescending or unAmerican about it.”

These words certainly remind us of the battles being fought today by women, the LGBT community and immigrants. The arguments in opposition to these groups are much the same as those used in the civil rights fights of the 1950’s and 1960’s.

So where did the Universalist Church stand on these issues? First, let us not forget that the Universalist Church ordained its first Black minister, Joseph Jordan, in 1889. Gerherdus Demarest, a former minister of our church, was a member of the seven-person committee that approved Jordan’s ordination.

In 1917, Universalists passed a massive “Declaration of Social Principles.” Part of that declaration stressed the equality of all individuals under God. This Declaration has been reiterated at a number of critical junctures in U.S. history. It was used to call for support of the creation of the United Nations, for example. It read:

“Whereas, Universalists profess to believe in the supreme worth of every human personality, as expressed in the historic Washington avowal of faith; and Whereas, persons of various ethnic and religious backgrounds seek the fellowship of the Liberal church; and Whereas, persons of these ethnic and religious backgrounds may from time to time wish to enter the ministry of the Universalist Church; Therefore, Be It Resolved that we reaffirm our historic position by urging our several churches and peoples to extend a warm welcome to both potential members and potential clergy regardless of race or color.”

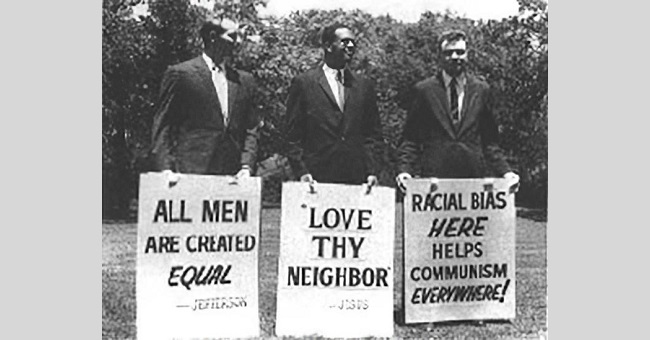

Image source: History 204: The Cold War.