by Mike Roberts, Church Historian.

We resume our examination of Arthur Nash, business entrepreneur and religious wanderer. He had opened a business as a clothing manufacturer and had built his company around the dictates of “The Golden Rule.” By 1924, Nash’s business was flourishing. The profits of that success were paid back to his workers. The worth of his company surpassed one million dollars and he returned the money from dividends to the workers in the form of higher wages and reduced hours. He especially cut the hours of women workers to 40 hours a week stating that these ladies needed to be home with their children to raise healthy future generations.

With all this success, Nash’s fame grew. He became popular as a public speaker and took every opportunity he could to spread the word about how he ran his business. He spoke at national organization meetings, church convocations, business conventions or wherever he could spread the message. J. C. Penney became a supporter and offered him opportunities to reach out to corporate America.

The message Nash delivered was simple. Treat your workers like you would want to be treated yourself. It was hard to argue against that message considering that Nash’s company had become one of the most successful in the United States. Its gross sales were huge and much of the company’s profits went back to his workers.

Part of the message that Nash wished to deliver was that of Universal Brotherhood. He believed that respect and dignity should be extended to all people regardless of race, creed, gender, national origins or religion. That theme had come to him partly through his involvement with the Universalist Church. He had traveled an ever-questioning, evolutionary religious path from his roots as a Seventh Day Adventist and that life-long quest had ended with the theme of Universal Brotherhood.

Nash also had to come to an understanding with the trade union movement. While he felt his own workers were well served without a union, he had gained great respect for Sidney Hillman the head of the garment workers union. He therefore urged his own workers to accept the union knowing it would have little effect on their economic standing or working conditions. He did feel that benefits would accrue to his company and the workforce as the union had much to offer in the way of technical advances in the field of clothing manufacture and worker safety. He and Hillman reached an agreement that would benefit both sides.

It should be noted that Sidney Hillman became a major player in unionization and politics during the 1920’s, 30’s and 40’s. He was able to throw considerable support behind Franklin Roosevelt and the New Deal, leading to a strong collaboration between the Democratic Party and the union movement.

As Nash spent more and more time touring and speaking, his business began to suffer. The management people he left to run the company lacked the Nash touch and production began to suffer. Nash also saw a decline in his health. He maintained a rigorous schedule and it began to take its toll. He was advised by friends to slow down but it was simply not in his nature to yield to forces that kept him from accomplishing his dreams. Nash briefly turned his attention to his business and the growth and profits picked up again.

To better get his message out to the public and his business peers, he began a newsletter identified as the “Nash Journal”. To edit the publication, he again turned to the First Universalist pulpit. He recruited John Edward Price to oversee the publication. Price at the time was the minister of our church. He left the church to assume his new duties which continued for about one year. He eventually moved to New York where he became the editor in chief in a publishing house and continued in that work until his retirement.

What ended the newsletter was Nash’s sudden demise. He was suffering from angina attacks and knew that his heart was weakened by his abundantly active life. He was urged to slow down but that simply was not in his nature. On October 28, 1927, he suffered a major heart attack and was rushed from his house at 830 Lincoln Avenue to Good Samaritan Hospital where he died two days later.

At the time of his death, he had 2,500 employees working in his factory in Cincinnati and a sales force of another 2,000 across the nation. He was paying his workers far above the standard of the day, working them fewer hours and yet was producing a quality line of clothing apparel that was earning his business huge profits every year. The business had reached these heights after starting 11 years earlier with a work force of about 25 people.

He had also done so by sticking rigidly to the application of the Golden Rule. This included five simple principals. These were “the strong shall help the weak; equal opportunity for all; opposition to war and power by force; no allegiance to partisan politics; and religious tolerance.”

Perhaps anticipating his passing, Nash had set up a Board of Directors to run the firm in case of his death or incapacity. It is not known what happened to the company immediately after his passing, but in the summer of 1929, the board sold nearly all of its stocks to a brokerage firm. This preceded by four months, the fall of the stock market that led to the Great Depression.

Both large Cincinnati papers announced his death on the front page. The headlines referred to him as “Golden Rule” Nash. Arthur Nash’s funeral was held at the Masonic Temple in Walnut Hills. It is also not known whether our church played any role in the funeral. Nash was buried in Spring Grove Cemetery. As late as 1943, Nash’s widow sent flowers in his honor to a ceremony being conducted at the Essex Street Universalist Church.

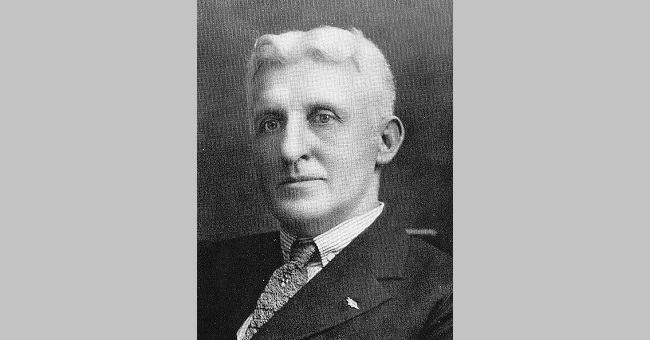

Main Image: Arthur Nash, circa 1927.

Image from Arthur Nash’s book The Golden Rule in Business, via Wikimedia Commons.