by Mike Roberts, Church Historian.

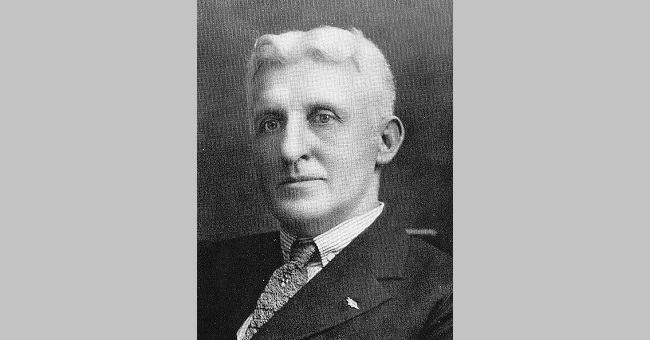

In researching the biographies of our past ministers, the name Arthur Nash was mentioned recurrently between 1915 and 1927. Researching the man has led to a fascinating story of Universalist thought and its application to society in general.

Arthur Nash was born in 1870 near Kokomo, Indiana. He was the son of fundamentalist Seventh Day Adventists. Raised and educated in the church, he eventually took a position teaching at the church’s theological seminary in Battle Creek, Michigan. There, he befriended a woman who was offering programs for discharged prisoners. These programs included Sunday church services which was anathema to Adventist thought. She was condemned to eternal damnation by the Adventists. Nash felt this to be wholly unfair and, in protest, he left the church forever.

Seeking to find himself, he adopted the life of a nomadic hobo and traveled throughout the Midwest seeking any odd job to sustain himself. He read books and studied people, all the while trying to determine where his religious belief lay. He eventually settled in Detroit, married and became a minister with the Disciples of Christ. His first calling was in Bluffton, Ohio. His connection with that faith did not last long as he conducted a funeral service of a man he believed to be kind and generous. He eulogized the man’s positive attributes but the deceased was a self-proclaimed non-believer. The church immediately asked for Nash’s resignation.

At a crossroads with a wife and three children, Nash decided to abandon the ministry and became a clothing salesman. He succeeded there, but felt he could run his own clothing manufacturing firm and thus opened a shop in Columbus. He experienced immediate success but his factory along with his finances were wiped out by the Great Flood of 1913. Not to be deterred, he moved to Cincinnati and opened a new shop which specialized in making made-to-order clothing, especially men’s suits.

Arthur Nash at some point became a member of our church and pastor Anthony Beresford invited him to deliver a sermon to the congregation. Nash had expressed opposition to Beresford’s position of supporting our entry into World War I but Beresford asked him to preach on the subject “What is Wrong with Christianity?” Nash stated in his sermon that he likened evangelists to maniacs saying that they pursued sawdust trails instead of seeking the paths of righteousness. Nash believed that organized religion was a contributing factor to many wars and especially World War I. In his sermon, he finished by stating that “There is nothing wrong with Christianity except that she stands outside the portals of our cold and selfish hearts knocking and pleading for entry.”

Nash’s pacifist stance was challenged when his eldest son enlisted in the Canadian Army and was critically wounded in France. His second son, feeling guilt, then enlisted in the U.S. Expeditionary Force and headed to Europe. Nash abandoned his pacifism and began selling Liberty Bonds and supporting the war effort in other ways. His business was neglected and neared bankruptcy.

His wounded son recovered, the war ended and Nash was at another crossroads. He decided to commit fully to his clothing business but with one rule in mind— the Golden Rule. He raised the salaries of his workers by two or three times their original rate, treated them with the utmost respect and was told that his business practices would plunge the company into debt within weeks. The opposite happened. The employees were so indebted to his kindness, the production of the workers increased exponentially and Nash found himself with a quality product sold at fair prices. His business boomed. He was determined to always run his life and his business with the Golden Rule as his guiding beacon.

The year 1920 witnessed massive labor unrest across the United States, especially in the garment industry. Unions were trying to organize but Nash’s workers were unmoved by the pressure to unionize since they were all making much higher wages than any workers in the industry. They crossed picket lines and continued to work during the strikes and Nash’s profits increased six-fold. He continued to hire new workers and increased the size of his operation at one time buying the old Moerlein Brewery to obtain the necessary space for burgeoning production. He was never openly hostile to the union movement as he knew how poorly most workers were treated. However, he felt paying good wages and treating the workers fairly—the Golden Rule—was the answer to the problem. He even issued an invitation to Sidney Hillman, head of the national garment workers union, to come to Cincinnati and address his workers. However, he soon had to rescind the invitation when it was discovered that the union had sent several highly inflammatory letters to his garment workers. His workforce demanded that the union should allow them and Nash to operate the factory in their own way.

It was during 1921 that Nash delivered another guest sermon at our church. He likened Jesus to a magnet. He demonstrated that random pieces of iron were in no way attracted to each other. But when a magnet was placed close to them, they all gravitated to the magnet as one. Also, minister Harold Guy Don Scott, who had taken the pulpit as our minister when Reverend Beresford left, stayed only several years before being lured to work for Nash at his company. He wrote newsletters for Nash and helped Nash in some of his efforts to communicate his labor ideas to the community. In 1926, Scott returned to the Universalist pulpit and served as a minister to many congregations before his retirement.

The unions were still hoping to draw the Nash workers into their organization and Nash was looking for ways to communicate his ideas to a greater audience. These issues and others will be discussed in Part II of the Arthur Nash story.

Image: Arthur Nash, circa 1927.

Image from Arthur Nash’s book The Golden Rule in Business, via Wikimedia Commons.