by Forrest Brandt

In May of 2017, I was driving around various WWi Battlegrounds in Belgium and France. Paschendale, the Somme, and the Marne were all clearly marked by a string of road signs that made them easy to locate. It was while traveling back from the battlefield of where was Vimy Ridge and the monument to the Canadian troops who fought there that I spotted a small road sign. I remembered enough of my high school French to pick out “Des Fraternisations” and deduce that this was marking the way to one of the several spots where British, French and German troops called their own armistice for Christmas of 1914.

These troops had been fighting since August and the trenches of each side stretched in one continuous line from the Ostende, Belgium in the west to the Swiss border in the east. The forces had suffered close to 3 million casualties and 400,000 dead in the five months of fighting. Propaganda on both sides painted the opponents as evil monsters, out to ruin civilization. Despite the sophistication of the weapons – rifled artillery, machine guns, rapid fire rifles, mines, and mortars – the fighting had often been at close quarters. There was no love to be lost between the two camps and between battles each side made life miserable for the other with artillery duels, raids, and snipers.

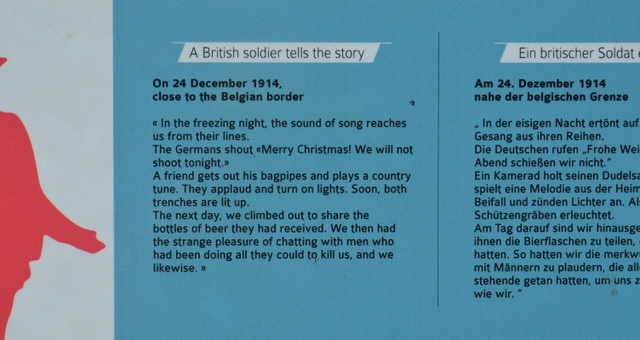

But something stirred within the troops of both sides as Christmas neared. While the high-ranking officers planned future battles, the enlisted soldiers, the non-commissioned officers, and junior officers who made up the front lines began to see the humanity in their enemy. The troops – not the commanders, not the politicians, not the diplomats – spent the week of Christmas communicating across no-mans-land. Out of this came a truce of sorts, a live-and-let-live attitude in which the troops allowed each side time to gather their dead and wounded. This expanded to visits between the trenches, exchanging and sharing of rations, wine, beer, and tobacco. At nights, the sides took turns singing Christmas carols. In some areas, soccer games broke out. A peace movement began to take form among the men on both sides as they questioned the causes and the purpose for the war.

Word began to reach the headquarters. Commanders on both sides became alarmed. Orders went out forbidding further “fraternisations” with the enemy. Units were ordered to attack and in a few cases artillery was ordered to fire into the meeting grounds, forcing the troops of both sides to retreat to their trenches. Investigations began to identify the leaders and organizers of the peace movement, followed by courts martial trials and punishments.

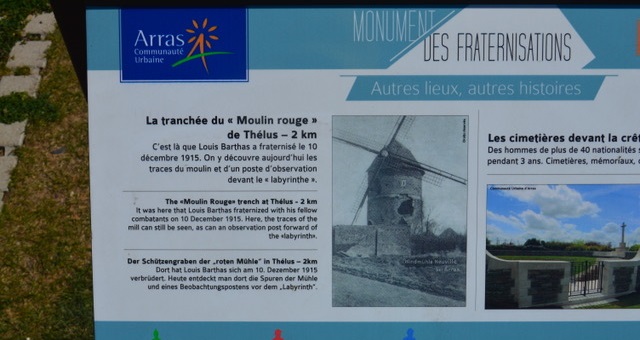

The common men, summoned to fight, suffer, and die, went on with their peace movement throughout the war. Both sides would see mutinies and rebellions before the war ended. Some Christmas truces came about in 1915, but by 1916 the level of fighting and the demonization of the “other” had become so intense that such truces became a rarity.

I mentioned that the sign I spotted was small. It was not on a major highway, more like a two-lane road between farms and small towns and villages. Unlike the signs guiding tourists to the major memorials and battlefields, it was written in French only. The 12-kilometer drive quickly tuned into 16 as the road forked left and right and no additional signs pointed me in the right direction. I finally flagged a postman and a funny conversation involving my few French verbs and nouns, his equal understanding of English, and lots of hand gestures ensued. He made me a crude map and I eventually reached my target.

The memorial was anything but grand. It had been created and dedicated in 2014, one hundred years after the truce took place. Less than fifty yards away was a large French military cemetery, probably containing the graves of many of the men who celebrated Christmas here. As I drove back to my hotel, I thought about the differences between the battlefield at Vimy Ridge and its magnificent memorial and Des Fraternisations. I considered how well the route was marked, the effort put into recreating the trenches, the modern museum and information program and compared it with afterthought shown at Des Fraternisations. Someone, actually lots of someones, wanted me to see Vimy Ridge, to sense that something important, something honorable, had taken place there. Those same someones didn’t really care if I found the tribute to Christmas and peace. It’s lack of majesty was supposed to tell me that this was something minor, a quirk in the history of World War I, nothing which should make me think of this as sacred and worthy of ceremony.

Photographs from in and around a monument to the WWII “Christmas Truce of 1914” in northern France.